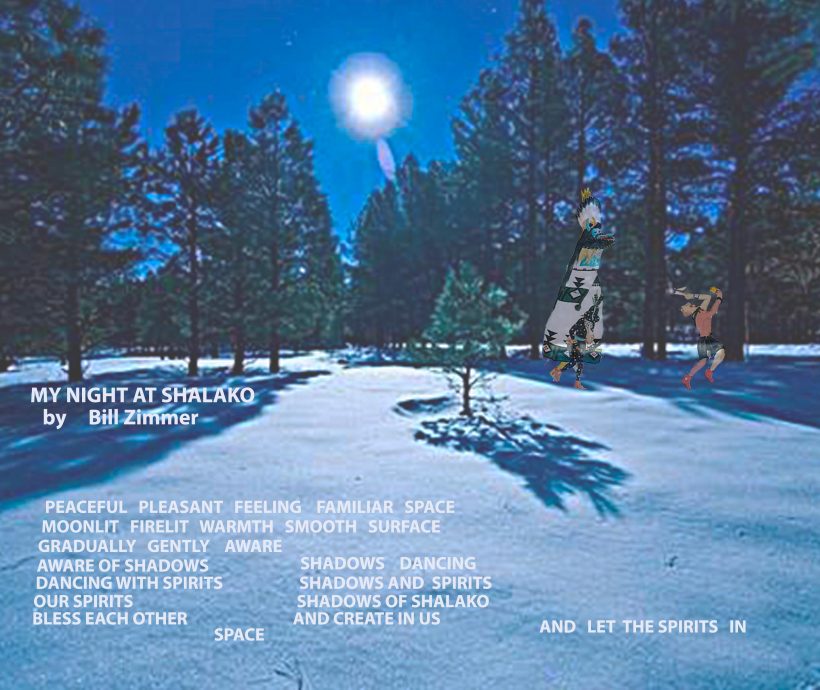

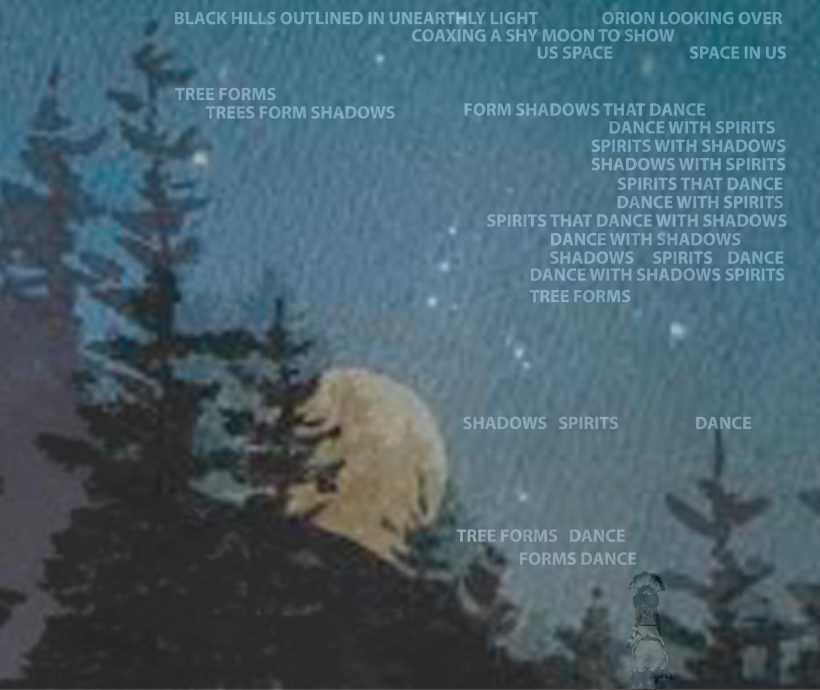

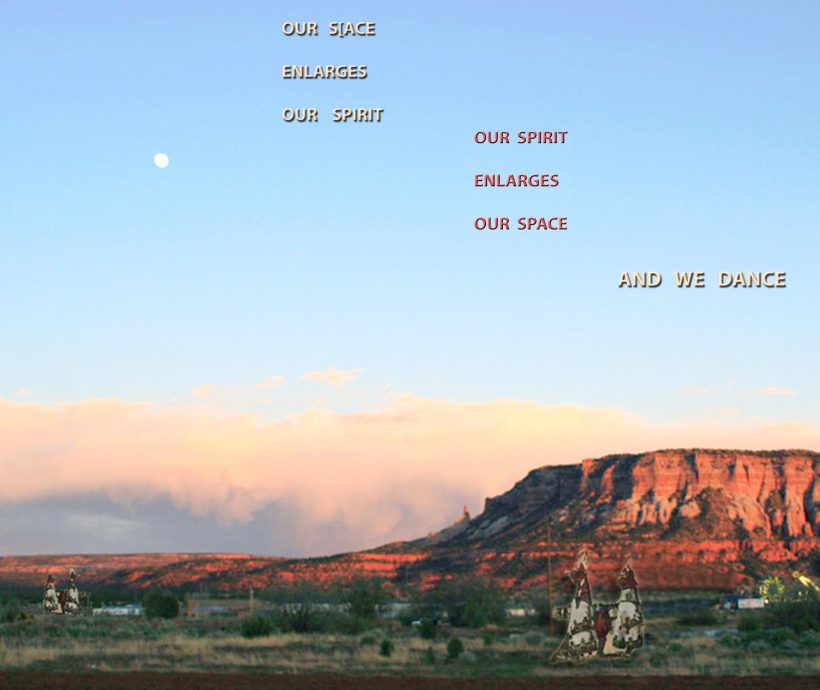

In early December of each year the Zuni people have a ceremony that lasts all night. This ceremony has so many elements that lots of other traditional ceremonies lack. There is humor, there is acknowledgement of the children, there is generosity in feeding the spectators and there is still the depth and spirituality that such ceremonies require. My experience there affected me greatly.

The Shalakos are messengers between the spirit world and our own. They are the spirit figures of the Zuni pantheon who mediate between humanity and the gods of rain and prosperity, the principal Zuni deities. (The word means ‘rain bringer’ in the Zuni language. Remember, the Zuni are a desert people—rain is a powerful force in their culture.) The Shalakos come to the human realm to collect the people’s prayers and take them back to the rainmakers at the end of the ceremony, thus connecting the mortal world to the spirit realm.

The Shalako ceremony, which lasts all night, ends in special Shalako houses built by the families sponsoring that year’s rite. When the Shalakos arrive in Zuni Pueblo, they plant prayer sticks in shrines and go to the ceremonial homes where they will spend the night. After the procession, the masked deities and their attendants arrive at the ritual homes where they conduct rites and are entertained.

The Shalako rite is one effort to put things back into harmony, and the Zunis believe that the benefits of the ritual accrue to everyone in the community, participants and spectators alike, and even to those beyond the pueblo borders. Between those conducting the ceremony and those for whom it’s performed, for instance, there’s a constant evocation of sharing. The Shalako prayers constantly speak of adding to someone’s heart—the center of the emotions and “profound thought”—and breath—the symbol of life, the way spiritual substance is communicated, and the source of mana, or divine power. The celebrants add to the hearts of their “fathers” (the gods), the gods to the hearts of the celebrants, the celebrants to those of the people, and so on. It’s a ritual passing of spiritual power. It’s further significant that, though the Shalako ceremony is specifically for Zunis, strangers (with the exceptions noted earlier) were welcome: “Verily, so long as we enjoy the light of day,” a Shalako prayer promises, “We shall greet one another as kindred”; another refrain vows: “And henceforth, as kindred, Talking kindly to one another, We shall always live.”

The Shalako ceremony is a loving enactment for the people of Zuni of their religion and their history. It’s a celebration of the coming new year and a prayer, expressed in action, for continued prosperity, fertility, and long life. It’s an offering to the gods in thanks for their favors in the past and to ensure their continuing benevolence and protection. But it’s also a ceremonial for the dead. At the winter solstice, the earth is on the verge of dying: the sun will withdraw from the skies for increasing parts of the day, the warmth and light will diminish, the plants and animals disappear from the land. But the Shalakos assure the people that it’s only a temporary withdrawal and that renewal will come again when the sun is reborn. A new year has begun.